Wednesday, May 9, 2012

The Avengers Disassemble the MetLife Building

Fare thee well, you who we once called the Pan Am. We hardly knew thee. Image from Comic Book Movie

Warning: This story contains light spoilers.

Recent fantasy films and TV shows have found ways to alter New York City through the creation of alternate universes. On Fox's Fringe, a parallel world features a New York where the World Trade Center wasn't destroyed, the Department of Defense is in a newly-bronzed Statue of Liberty, and Robert Moses never drove the Dodgers from Brooklyn. (The show also showed us what the skyline might look like with some Antonio Gaudi architecture.)

Comic book movies delight in showing super villains destroying the city -- this summer's 'The Dark Knight Rises' blows up bridges and ravages Federal Hall, while 'The Amazing Spider-man' will trash Midtown -- and sometimes they even re-write history itself.

In 'Captain America: The First Avenger', the title character, a resident of Red Hook, discovers underground government laboratories in downtown Brooklyn during World War II. Elsewhere in this Marvel Comics timeline, Moses' World's Fair of 1939-40 was such a smashing success that Tony Stark (aka 'Iron Man') turns the site into a year-round glittering expo of technology!

The latest Marvel adventure 'The Avengers' takes a more proactive approach to revising the city landscape, as though the entire film was a surly New Yorker architecture critic.

Thanks to the Commissioners Plan of 1811, allowing for a grid striped with long uninterrupted canyons, grotesque alien beings from Asgard can fly down the avenues unabated, wrecking havoc through Manhattan -- Park Avenue in particular. Fortunately our heroes gather at Grand Central Terminal's traffic overpass, a critical location that they turn into a picturesque battleground. (Honorary Avenger Cornelius Vanderbilt, or at least his old statue from St. John's terminal, stands resolutely in the background, ready to employ his superpower of acquiring railroads.)

But one famous New York building is notably missing from these shenanigans. Stark, played by Robert Downey Jr., has constructed an energy-efficient new supertower for Stark Industries right on Park Avenue itself. To build this, he has clearly gotten permission from the city to methodically dismantle the MetLife Building (the former Pan Am Building).

The filmmakers have specifically chosen not to merely erase the MetLife Building, but to specifically display it being taken apart. The building is shown greatly reduced in height, decorated with cranes disassembling it like a tinker toy.

While other buildings enjoy the glamour of being reduced to rubble by gigantic mechanical space fish, the MetLife is ignobly taken apart to be replaced by an even taller, uglier structure. In fact, the dismantling looks a bit like this picture, an image of the Pan Am Building during construction in 1969:

(You can find a few more interesting construction pics here.)

The MetLife Building is easily one of the most disrespected structures in Manhattan and has been almost since the beginnings. Ada Louise Huxtable famously wrote: "A $100 million building cannot really be called cheap. But Pan Am is a colossal collection of minimums."

According to author Meredith Clausen, "The Pan Am Building and the reaction to it signaled the end of an era. Begun when the modernist aesthetic and the architectural star system ruled architectural theory and practice, the completed building became a symbol of modernism's fall from grace."

Its broad-shouldered silhouette calls a halt to Park Avenue in a dated style that hovers between two Beaux-Arts structures (Grand Central to its south, the Helmsley Building to its north). Yet people blame the building for somehow 'ruining' Park Avenue -- when the two other structures already blocked it -- and its sly octagonal shape today makes it one of New York's more interesting Brutalist-style examples.

Modernism happened, and if you use the same criteria that we might apply to other treasured New York structures, then the MetLife Building is a unique and exemplary building. But can you ever imagine a time when the MetLife Building might ever be landmarked?

This is what I was thinking while Thor and the Hulk were tearing into alien lifeforms.

But 'The Avengers' isn't entirely disrespectful of architecture. In fact, the Chrysler Building is practically fetishized as an ideal view from the newly built penthouse of the Stark Building.

Its antenna spire, which makes it New York's fourth largest building, is even utilized by Thor in the battle to save the Earth. William Van Alen, the building's architect, would have been quite amused. This very spire was hoisted to the top of the structure from within the building itself in October 1929, a surprise accessory that allowed the Chrysler to take the title of New York's tallest building from 40 Wall Street.

For more information on the controversies surrounding the MetLife Building, check out the 'illustrated' version of our podcast (Episode #61). Download it from iTunes or directly from here.

Pic above courtesy Bleeding Cool

Posted by

TUTULAE

Tuesday, May 8, 2012

Who are Barnes and Price? And other notes from the podcast

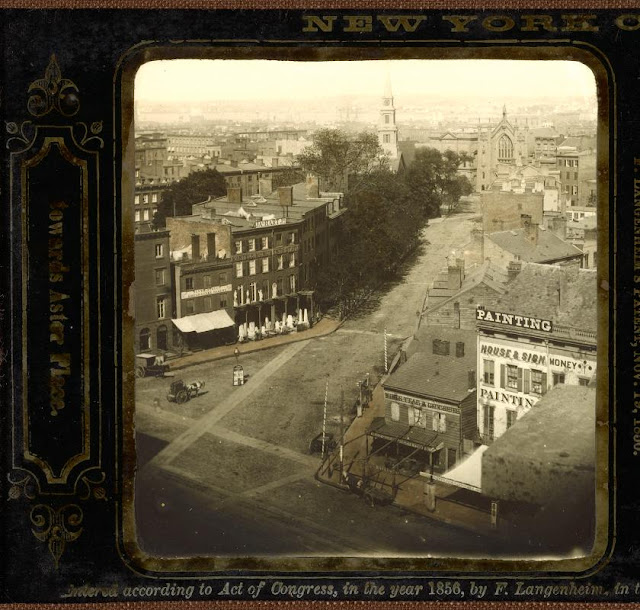

Stuyvesant Street in 1856, an aberration to the city grid plan thanks in part to the presence of St. Mark's Church and its well-established churchyard. The small building in the foreground is where the St. Mark's Bookshop stands today. You can see the steeple of St. Mark's. Hmm, what what's the other

church in the background? (Pic courtesy East Village Transitions)

Some notes on our podcast, Episode #139: St. Mark's-in-the-Bowery

THANK YOUS: For of all, we'd like to thank Rev. Winnie Varghese and Roger Jack Walters from St. Mark's Church for telling us some wonderful stories on a sunny Sunday afternoon as volunteers worked busily to repaint that 1838 iron fence. This is one landmark is really good hands!

THE MYSTERY OF BARNES AND PRICE: There was once a second cemetery one block north of St. Mark's that contained the bodies of less wealthy individuals in the community. In September 1864, their bodies were exhumed and moved to Evergreen Cemetery at the border of Brooklyn and Queens. The New York Times report on the exhumation mentions two individuals in particular: "The remains of two dramatic notables, BARNES and PRICE, of the Old Park Theatre, have been removed from this cemetery."

The Park Theatre (pictured at right) is considered New York's first great theater, sitting on Park Row in the days before there was a City Hall, a Printer's Row or anything else recognizable or familiar about that area today. The stage entertained British officers during the Revolutionary War, and in the early 19th century presented entertainment of the highest class.

The PRICE buried in the old St. Mark's Cemetery is most likely its former manager Stephen Price, who specialized in importing British stage stars for their American debuts. One of those was Julius Brutus Booth, who debuted Shakespeare's Richard III here in 1822. Booth's children Edwin Booth and John Wilkes Booth would enter the acting profession in the mid-19th century.

But who's the BARNES? Most likely it was English actor John Barnes who frequented the Park and died in 1841. However, his wife Mary, billed as Mrs. John Barnes, was in many ways a bigger star, the resident 'heavy-tragedy lady' who made here debut here in 1816. The two often appeared on stage together -- husband for the comedy, wife for the drama.

Mary Barnes outlived her husband by a quarter century, remarrying and becoming a successful theater manager in her own right. She died in the same year that her first husband's body was moved to Evergreen. An assessment of her career: "In melodrama and pantomime her action was always graceful, spirited and correct." [source]

FURTHER LISTENING: Although Augustus Stuyvesant was the last living direct descendant, there are others named Stuyvesant that trace their lineage to Rutherford Stuyvesant. To find out why this doesn't quite count, listen in to my podcast on Rutherford's pet project The Stuyvesant apartment, New York's first of its kind. (Episode #131: The First Apartment Building).

We tell a ghost story about Peter Stuyvesant and St. Mark's Church In-The-Bowery in our most popular of our ghost story podcasts. (#91 Haunted Tales of New York)

And of course, for more information on Peter Stuyvesant himself, we devoted an entire podcast to the director-general back in 2007. (Episode 14# Peter Stuyvesant)

SLIP UPS: This weeks verbal slip-ups include me saying 'St. Mark's ON-the-Bowery' twice (it's referred to in many ways, but never that).

Posted by

TUTULAE

Monday, May 7, 2012

UK Magazine: 'Out In The City' Madonna

The new issue of 'Out In The City' magazine – with #Madonna on the cover – is out now in London!

#Madonna #LoveSpent #MDNA Tour

Floating about are some weird recordings. Make what you will of them. I love it all!

Posted by

TUTULAE

'Mad Men' notes: The delirious world of Off-Off-Broadway

Radical thoughts, limited spaces: a performance at the Caffe Cino. Photo by Ben Martin (from an excellent website by Robert Patrick about this important off-off-Broadway site)

WARNING The article contains a couple spoilers about last night's 'Mad Men' on AMC. If you're a fan of the show, come back once you're watched the episode. But these posts are about a specific element of New York history from the 1960s and can be read even by those who don't watch the show at all. You can find other articles in this series here.

Megan might be Sterling Cooper Draper Pryce's hottest new pitchwoman, but deep in her heart of delicate French extraction, she wants to be an actress. And in last night's show, she steals away to an audition of an unnamed off-off-Broadway production. She didn't get the part, but the experience leads her to make a jarring decision.

This wasn't merely a plot contrivance, but rather another use of New York geography to delineate character. Don Draper was busy at Danny's Hideaway, a Midtown East restaurant along famed 'Steak Row' shimmering with late 50s -- and, by 1966, ever fading -- glamour. Megan's off-off-Broadway audition could only be one place, and that was downtown below 14th Street, in the thriving epicenter of New York counter culture.

Aspiring performers have made New York their destination for fame since the late 19th century with the birth of the Broadway theater circuit. By the 1950s, playwrights and producers who challenged the preconceptions of standard, mainstream theater found homes for their work off Broadway both literally and metaphysically. The art of theater could now be explored for smaller crowds and with smaller budgets.

But even off-Broadway was not immune to financial realities. By the end of the decade, the popularity of off-Broadway created a parallel industry, "a smaller-scale version of Broadway itself." [source] If you were to look back at the greatest off-Broadway hits of this era (plays by Tennessee Williams and Edward Albee, musicals like Threepenny Opera) you'd notice that most of them have had subsequent Broadway debuts. Indeed, off-Broadway continues to be a sort of a minor league tryout for future Broadway shows.

By the 1960s, unconventional creative voices were emerging that seemed positively alien even in that world. What do you call the alternative to something that was itself the alternative? Although Village Voice critic Jerry Tallmer is credited with coining the phrase 'off-off-Broadway', the phrase might have sprung up naturally the first time audiences came in contact with the early works of this field -- modest, broken-down, difficult and experimental shows eager to discard every theatrical trapping that had built up for the past four hundred years.

The first 'true' off-off-Broadway performance, according to Tallmer's fellow Voice critic Michael Smith, was a surreal revival of Ubu Roi, performed at a Bleecker Street coffeehouse in 1960. Theatrical experimentation complimented the Village music scene nicely, as even the smallest venues could now host a production. Only in this new creative world could a cramped, smoke-filled coffeehouse like Caffe Cino, at 31 Cornelia Street, become center stage for a new theatrical revolution.

If the art was nontraditional, so too were the venues. Two churches became important homes for alternative theater in the early 1960s and they remain so to this day. Judson Memorial Church, off Washington Square, may seem austere with its elegant Italianate bell tower, turned its meeting room into an off-off-Broadway stage in 1961. And, of course, St. Marks-in-the-Bowery, took a page from its own 1920s radical bohemian past to become home to the Poetry Project and Theater Genesis (performing sometimes sexually explicit plays in the churches parish hall). Above: A poster for Theater Genesis

But just as many pivotal and provocative voices of off-off-Broadway were developing further east, in an area of the Lower East Side heavily influenced by Greenwich Village counterculture idealism and referred to by the mid-60s as the East Village. The chief among these, Ellen Stewart's mold-breaking La Mama Experimental Theatre, opened in 1961 and rejected most theatrical instincts, featuring only new plays in a stripped-down, almost barren theatrical space. Pictured above: Ellen Stewart in 1970. Picture courtesy TCG

By 1966, off-off-Broadway became a banquet of experimental ideas, spaces for gay, feminist and African-American playwrights and performers. In effect, the opposite of a certain ad agency, where creative flowering is hindered by the whims of client preference and the banality of subject.

Posted by

TUTULAE

Labels:

classic theaters,

East Village,

La Mama,

Mad Men,

off-Broadway,

off-off-Broadway,

St. Marks on the Bowery,

Village Voice

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)