Last year at this time, I did a podcast on Mark Twain in New York and featured this map of notable places Twain worked, lectured, lived and played. Today is the author's birthday -- he was born 176 years ago -- so I thought I'd reprint the map in case you wanted to revisit a few places in his honor, with stops in Manhattan, Brooklyn and the Bronx. (And even places on Governors Island and Randall's Island!) The three key destinations are his two residences near Washington Square Park and his cliff-side respite up at Wave Hill in Riverdale, Bronx. But the boarding house where he first lived, as a teenager? It's on Duane Street, in today's TriBeCa.

View Mark Twain in New York in a larger map

He also seemed to have had an altercation on a streetcar in 1890 that rankled him most severely, according to a letter he wrote to the New York Sun. The author jumped on the streetcar at Sixth Avenue and 42nd Street. An excerpt:

"Of course there was no seat -- there never is: New Yorkers do not require a seat, but only permission to stand up and look meek, and be thankful for such little rags of privilege as the good horse-car company may choose to allow them

...After a moment, the conductor, desiring to pass through and see the passengers, took me by the lappel and said to me with that winning courtesy and politeness which New Yorkers are so accustomed to: "Jesus Christ! what you want to load up the door for? Git back here out of the way!".....This conductor was a person about 30 years old, I should say, five feet nine, with blue eyes, a small, dim, unsuccessful moustache, and the general expression of a chicken thief -- you may probably have seen him.

I said I would report him, and asked him for his number. He said, in a tone which wounded me more than I can tell, "I'll give you a chew of tobacco."

I went up to Sixth avenue and Forty-third street to report him, but there was nobody in the superintendent's office who seemed to want to converse with me. A man with "conductor" on his cap said it wouldn't be any use to try to see the President at that time of day, and intimated by his manner, not his words, that people with complaints were not popular there, any way.

So I have been obliged to come to you, you see. What I wanted to say to the President of the road was this -- and through him say it to the President of the elevated roads -- that the conductors ought to be instructed never to swear at country people except when there are no city ones to swear at, and not even then except for practice. Because the country people are sensitive. Conductors need not make any mistakes; they can easily tell us from the city people. Could you use your influence to get this small and harmless distinction made in our favor?"

Oh, Samuel.

Courtesy Twain Quotes

Wednesday, November 30, 2011

Tuesday, November 29, 2011

Finally, the Bowery Boys look good on mobile devices!

Not sure why this took me forever to set up, but you can finally read our blog on your mobile devices without any awkward scrolling or squinting your eyes. Just visit www.boweryboyspodcast.com (www.theboweryboys.blogspot.com) on your phones to check it out!

I'm also in the planning stages of creating an actual mobile app, but until that makes an appearance, just find us on your favorite mobile search engine....

I'm also in the planning stages of creating an actual mobile app, but until that makes an appearance, just find us on your favorite mobile search engine....

Posted by

TUTULAE

Monday, November 28, 2011

Relaxation in Astoria, in the lap of Queens history

You'll still find a few free-standing homes on this tip of Astoria. Queens -- traditionally called Hallet's Cove -- but you won't find the one above, a veritable (if ramshackle) plantation getaway as photographed by Berenice Abbott in 1937. The caption of this picture places this house in the hands of Joseph Blackwell, an ancestor of an early settler to this area. Another descendant, Col. Jacob Blackwell, remained loyal to the British during the Revolutionary War; it was his home, named Ravenswood, that gave its name to the neighborhood just south of here.

This was one of many such multi-story single-family homes that lined Franklin Street, in the shadow of 'The Hill', an elegant neighborhood in the days soon after the borough of Queens was created and incorporated into New York City in 1898. This property was but a short stroll from the original estate of Stephen Ailing Halsey, the founder of the original village of Hallets Cove. The village was later renamed Astoria in order entice John Jacob Astor to invest here. Barely interested, Astor did manage to give Halsey $500.

Franklin was later ingloriously renamed to 27th Avenue.

Wednesday, November 23, 2011

Happy Thanksgiving Masking: The pleasures of mischief, featureless masks and cross-dressing children!

No, these children have not gotten their calendars confused. One early American Thanksgiving tradition amongst rascals and rowdies involved goofy costumes and disguised faces. Sometimes called 'Thanksgiving masking', the strange practice stemmed from a satirical perversion of poverty and an ancient tradition of 'mumming', where men in costumes floated from door to door, asking for food and money, sometimes in exchange for music. The annual Philadelphia Mummers Parade traces back to the original tradition which some believe began in the 17th century.

By the 1800s, those going door-to-door asking for handouts were most likely homeless and poor. This seems to have inspired a children's tradition not unlike modern trick-or-treat. "Every street had its band of children," proclaimed the 1901 Tribune, "dressed as ragamuffins, who kept in the open air for hours."

Newspapers advertised 'Thanksgiving masks' and 'lithographed character masks' for the tots. These featureless disguises were often sold in candy stores alongside holiday related treats like spiced jelly gums, opera drops, crystallized ginger and tinted hard candies.

"This play of masking is deeply rooted in the New York child," said Appleton's Magazine in 1909. "All toy shops carry a line of hideous and terrifying false faces or 'dough faces' as they are termed on the East Side."

Boys frequently wore girls clothing on this occasion, "tog[ging] themselves out in worn-out finery of their sisters" and spending their afternoon "gamboling in awkward mimicry of their sisters to the casual street piano."

The New York Times in 1899 found the streets filled with costumed tricksters that Thanksgiving. "There were Fausts, Filipinos, Mephistos, Boers, Uncle Sams, John Boers, Harlequins, bandits, sailors... In poorer quarters a smear of burned cork and a dab of vermilion sufficed for babbling celebrants."

Those that benefited most -- outside of the costumed children, obviously having a ball -- were the candy stores that both sold the masks and provided the sweets distributed to the little devils. In particular, Loft Candy stores, headquartered at the corner of West 42nd Street and Eighth Avenue, ran spectacular ads filled with Thanksgiving themed candy treats.

In general however it's difficult to find too much enthusiasm for this unsavory tradition in newspapers of the day. Thanksgiving was (and continues to be) one of the most austere holidays. Poor, cross-dressing, shoddy-garbed children in masks flew in the face of this perception and was generally discouraged. Editors preferred to focus on family gatherings, recipes and table placements, not only out of social convention but on the behest of advertisers, who made more money selling turkey and china than cheap masks.

While the chaotic tradition was associated with poverty and mischief, some educators saw a bright side to the tradition, especially in the waning years of World War I. One writer on early Kindergarten practices suggested that "the masking on the streets of Thanksgiving Day ... has its redeeming quality, in reminding the children of our dear soldiers' need for real masks." They would be referring to gas masks. Educational indeed!

Such mischief, not surprisingly, occasionally went out of control. For instance, the New York Tribune in 1907 reports a poor lad "in mask and fantastic garb" who was hit by a train and had his leg amputated.

With the rise and commercialization of Halloween, the practice of Thanksgiving masking seems to have died out. And the entrance of the Macy's Thanksgiving Day parade in 1924 certain gave focus to the city's need for costumed celebration.

NOTE: These photos are from the Library of Congress. As such, the locations are unmarked. Most likely they are all of New York children, but a few may be children from other cities in delirious states of costume. (The top photo is courtesy Shorpy)

Happy Thanksgiving!

Tuesday, November 22, 2011

Notes from the podcast (#131) The First Apartment Building

The Stuyvesant Apartments in 1934, already being dwarfed with a newer structure on the right. Please note the ornate entrance to the Third Avenue elevated train to the left of the picture, as well as the streetcar tracks, no longer in use along East 18th Street in 1934, running down the cobblestone street. And I'm fairly sure that's a taxicab in the foreground.

Here are some notes on podcast #131: The First Apartment Building. To listen to the show, download it from iTunes or from here. And for those who have listened, thanks for making it one of iTunes top three individual programs in the travel/places podcasts section this weekend!

The Distinction of the 'First'

How did the Stuyvesant Apartment become known as the true 'first' apartment? After all, it's not like there was a banner over the door proclaiming "Welcome to the first apartment building ever! Come inside!" Urban dwellings were being developed of all shapes and sizes. As I mentioned, there's not much that technically separates a tenement from an apartment, if you subtract social class and building amenities. There were indeed 'fancy' tenements. Some of those buildings are still around today and serve as rather lovely renovated apartments.

Author Elizabeth Collins Cromley (more on her later) suggests there were a couple other buildings in New York City that could have held this title built earlier, including another that Richard Morris Hunt built on Wooster Street. Those candidates, however, were smaller and less profitable. (One was even refashioned as a hotel.) The Stuyvesant was ambitious in size, glorious in architecture and glittering in its notable residents.

Below: Original drawings of the Stuyvesant Apartments, done by the Historic American Buildings Survey, courtesy Library of Congress

The Other Stuyvesant?

The research for this show became trickier once I realized there was another apartment building that was sometimes referred to the Stuyvesant just a few blocks away, and some scholars have confused the two in their research. For instance, I was quite excited to learn that Clara Clemens, the daughter of Mark Twain, lived at the Stuyvesant until I realized it was most likely the other Stuyvesant. (This author erroneously combines the two structures.)

The second building is right off of Stuyvesant Square, originally addressed 17 Livingston Place. That street no longer exists. Or to quote the wonderful Old Streets blog: "On December 3, 1953, in one of the goofier acts of the City Council, it changed the name of Livingston Place (on the east side of Stuyvesant Square) to Nathan D. Perlman Place and simultaneously--perhaps to mollify any offended Livingston descendants--changed the name of Birmingham Street to Livingston Place. The compensation was short-lived. The new Livingston Place was demapped in 1962."

That building at 17 Livingston Place (valued at drastically less than the Stuyvesant) was apparently demolished too; Beth Israel Medical Center facilities have taken up that side of the square since the late 1910s.

That Stuyvesant Name!

The apartment structure was constructed on old Stuyvesant property. Check out this map of the borders of Stuyvesant farm, which consumes much of today's East Village and the area dominated by Stuyvesant Town/Peter Cooper Village.

Rutherford Stuyvesant, creator of this luxury apartment, died in Paris, on July 4, 1909. His first wife, a member of the influential Brooklyn clan the Pierreponts, died a few years after the construction of the Stuyvesant Apartments. In 1902 Rutherford took a second wife whose name certainly equaled his own in terms of drama -- the Countess Mathilde Elizabeth de Wassanaer [More bio details here]

Stuyvesant built a lavish mansion near Allamuchy, New Jersey called Tranquility Farms, populating the surrounding land with imported trees and animals. The mansion was consumed in fire in 1959. Although the ruins were demolished, many other ancient buildings on the property remain intact. Rusty Tagliareni has taken some fascinating, haunting photos earlier this year of the ruined area. Take a gander here.

Below: Inside the lobby of the Stuyvesant, circa 1934.

For further reading

There's a great many books on the history of New York real estate. Definitely invaluable to me this time was Elizabeth Collins Cromley's 'Alone Together: A History of New York's Early Apartments' and also Steven Gaines' 'The Sky's The Limit'. I learned about the inestimable Mrs. Custer from Shirley A. Leckie's book 'Elizabeth Bacon Custer and the Making of a Myth.'

Photos above courtesy the Library of Congress

Posted by

TUTULAE

Monday, November 21, 2011

"New York was his town, and it always would be...”

I hope you all caught part one of PBS's Woody Allen documentary last night. Part of the American Masters series, it was a beautiful tribute, not just to the filmmaker, but to 70s New York, and in particular, Woody's old neighborhood -- Midwood, Brooklyn.

The second part concludes this evening at 9pm EST. I'll be on Twitter during the broadcast (@boweryboys) posting trivia and little pertinent factoids if you'd like to follow along.

Tomorrow I'll have notes, additional information and further reading regarding last week's podcast on the Stuyvesant Apartments.

Friday, November 18, 2011

The Stuyvesant, New York's first apartment building: Imported luxury style for a new middle class

The creation of 'acceptable' communal living: The Stuyvesant Flats, at 142 East 18th Street, designed by Richard Morris Hunt, photographed by Berenice Abbott.

PODCAST Well, we're movin' on up....to the first New York apartment building ever constructed. New Yorkers of the emerging middle classes needed a place to live situated between the townhouse and the tenement, and the solution came from overseas -- a daring style of communal and affordable living called the 'apartment' or 'French flat'.

The city's first was financed by Rutherford Stuyvesant, an old-money heir with an unusual story to his name. He hired one of the upper class's hottest architects to create an apartment house, called the Stuyvesant Apartments, with many features that would have been shocking to more than a few New Yorkers of the day.

The building's first tenants were sometimes well-known, often artists and publishers, and almost all of them with a fascinating story to tell. Listen in to hear about the vanguard first renters of this classic, long-gone building.

You can tune into it below, download it for FREE from iTunes or other podcasting services, or get it straight from our satellite site.

Or listen to it here:

The Bowery Boys: The First Apartment Building

I have been unable to find any portraits of Mr. Rutherford Stuyvesant (aka Stuyvesant Rutherford), the man who financed the Stuyvesant for $100,000. However I have found a picture of Mrs. Rutherford Stuyvesant, who doesn't look like the kind of lady to mettle around in her husband's affairs. She would not have found the apartments which bore her name very accomodating. Many, many others did. (Courtesy LOC)

The tenacious Elizabeth 'Libby' Custer, photo taken in 1876, the year her husband was killed at the Battle of Little Bighorn. Mrs. Custer moved into Stuyvesant and successfully led her crusade to rehabilitate her husband's reputation.

Maggie Custer Calhoun, younger sister to General Custer, lived with her sister-in-law at the Stuyvesant before embarking on a successful career as an elocutionist.

The landscape painter Worthington Whittredge also resided here. In fact, he beamed about it in his autobiography: "I was one of the first to subscribe for an apartment in this house, which was to be erected in 18th Street near Third Avenue and Stuyvesant Square."

Earlier in his career, Whittredge posed as George Washington while Emanuel Leutze painted 'Washington Crossing The Delaware'. (Worthington is quite comfortable on both sides of the easel The painting below is by William Merritt Chase.)

In its later years, the Stuyvesant was used as the set for a pivotal scene in the Oscar-nominated film noir 'Kiss of Death' starring Richard Widmark. Needless to say, this sort of activity very rarely went on at the Stuyvesant.

View Larger Map

Posted by

TUTULAE

Thursday, November 17, 2011

If you lived here, you'd be home by now....

The Navarro Flats, once at Seventh Avenue and 59th Street, was an early pioneer of luxury apartment living along Central Park South. Although this stunner, by Spanish architect José Francisco de Navarro, is long gone, it set the pace for acceptable living on the park's outskirts. Tomorrow, I'll present another vanished classic of the apartment scene, one of the first buildings to indoctrinate New Yorkers on the joys of luxury communal living. The new podcast will be ready for download by this evening!

By the way, the Navarro had some very well-known financial troubles, more of which you can read about here.

Pic courtesy NYPL

Tuesday, November 15, 2011

Museum mania: the refurbished New York Historical Society, and a stunning debut at the Brooklyn Navy Yard

Anchors Aweigh: A museum finally opens in one of Brooklyn's most restricted outposts

The Brooklyn Navy Yard finally got the museum it deserves this past weekend with the opening of BLDG 92: Brooklyn Navy Yard Center, a badly needed introduction to this long-restricted yet important component of New York history.

The environmentally-friendly new center is affixed to the 1858 Marine Commandant’s residence in one of the city's better old-new hybrids, and visitors are constantly and playfully reminded of the building's forward-thinking approach. (Bathrooms supplied with rainwater!) But it's the history of the Navy Yard -- within the context of Brooklyn's own history -- that's the main attraction here.

The first floor provides an exhaustive but well-spun timeline, weaving the Navy Yard's beginnings into the context of America's own naval history. On opening weekend, there was a sailor and a Rosie the Riveter-type on hand, and even they seemed delighted to play around with the interactive consoles. The second floor further describes the day-to-day workings, with kooky artifacts (old whiskey bottles!) and curious trivia (the Yard was once overrun with cats!) mounted to the walls.

On the third floor is a display on the Navy Yard in wartime, its closure in the 1960s and its transformation into an enclosed industrial park. While I hardly found its first-floor displays of modern products produced at the Yard to be awe inspiring, it's balanced by a moving, even disquieting display of photography on the third floor. The show 'War Photographers', is in memory of Tim Hetherington, the photojournalist (and co-director of the film Restrepo) killed in Libya several months ago. Both he and the gallery's curator Christopher Anderson have a unique connection to the Navy Yards that reinforces this once mysterious place as a vital part of the city today.

Given that admission is free (I believe for the next few weeks, but possibly longer, check their website for more info), this is pretty much a must-see for history buffs and a seamless blend of displays for adults and children. Imagine what this kind of ingenuity could do for the nearby Admirals Row?!

If any place needed a thorough renovation, it was the New York Historical Society. The museum, one of the city's longest enduring cultural institutions, contains New York's greatest treasures. Until recently, however, it's been a tad unpleasant to enjoy many of them.

Not that the Historical Society hasn't put on spectacular exhibits and lectures in the past. For instance, I consider Alexander Hamilton show from 2004 one of my inspirations for creating this podcast and blog in the first place. But the exhibit spaces were often stuffy with a lack of open space, with oversized exhibits twisting down corridors. The museum's prized artifacts were often hard to find or dimly presented.

The lavish new first-floor renovation dispenses with any further obscurity. Here in plain day are all the greatest hits of the museum, boldly presented on the wall or within nooks under foot. In fact, one modern treasure -- Keith Haring's whimsical ceiling from the Pop Shop -- hangs above the ticket booth. To find this just several feet from Gouverneur Morris's wooden leg and the dueling guns of Hamilton and Aaron Burr makes for a grand and innovative statement.

Finally, the NYHS makes a hard turn for the modern. The Robert H. Smith Auditorium now shows 'New York Story', whisking through New York history with lighting effects, constantly moving screens and a projection of almost IMAX-like proportions. (I was genuinely surprised we didn't get those 4-D effects like rain mist and soap bubbles, but then that would ruin the fancy new auditorium seating.)

A new 'sculpture court' showcases a spectacular rarity (a Revolutionary-War era Torah) while the children's museum downstairs has been heavily revised and seems a genuinely fun experience. A scarlet-hued first-floor gallery presents the NYHS's greatest paintings more accessibly than before. Upstairs are three new exhibitions, and of course, still on the fourth is the quirky, oddly charming Henry Luce III Center for the Study of American Culture, essentially the most meticulously arranged attic in the city.

For more information visit their website: New York Historical Society. The museum is open until 8pm on Friday nights and now you can dine at a Stephen Starr restaurant there, Caffe Storico.

The Brooklyn Navy Yard finally got the museum it deserves this past weekend with the opening of BLDG 92: Brooklyn Navy Yard Center, a badly needed introduction to this long-restricted yet important component of New York history.

The environmentally-friendly new center is affixed to the 1858 Marine Commandant’s residence in one of the city's better old-new hybrids, and visitors are constantly and playfully reminded of the building's forward-thinking approach. (Bathrooms supplied with rainwater!) But it's the history of the Navy Yard -- within the context of Brooklyn's own history -- that's the main attraction here.

The first floor provides an exhaustive but well-spun timeline, weaving the Navy Yard's beginnings into the context of America's own naval history. On opening weekend, there was a sailor and a Rosie the Riveter-type on hand, and even they seemed delighted to play around with the interactive consoles. The second floor further describes the day-to-day workings, with kooky artifacts (old whiskey bottles!) and curious trivia (the Yard was once overrun with cats!) mounted to the walls.

On the third floor is a display on the Navy Yard in wartime, its closure in the 1960s and its transformation into an enclosed industrial park. While I hardly found its first-floor displays of modern products produced at the Yard to be awe inspiring, it's balanced by a moving, even disquieting display of photography on the third floor. The show 'War Photographers', is in memory of Tim Hetherington, the photojournalist (and co-director of the film Restrepo) killed in Libya several months ago. Both he and the gallery's curator Christopher Anderson have a unique connection to the Navy Yards that reinforces this once mysterious place as a vital part of the city today.

Given that admission is free (I believe for the next few weeks, but possibly longer, check their website for more info), this is pretty much a must-see for history buffs and a seamless blend of displays for adults and children. Imagine what this kind of ingenuity could do for the nearby Admirals Row?!

If any place needed a thorough renovation, it was the New York Historical Society. The museum, one of the city's longest enduring cultural institutions, contains New York's greatest treasures. Until recently, however, it's been a tad unpleasant to enjoy many of them.

Not that the Historical Society hasn't put on spectacular exhibits and lectures in the past. For instance, I consider Alexander Hamilton show from 2004 one of my inspirations for creating this podcast and blog in the first place. But the exhibit spaces were often stuffy with a lack of open space, with oversized exhibits twisting down corridors. The museum's prized artifacts were often hard to find or dimly presented.

The lavish new first-floor renovation dispenses with any further obscurity. Here in plain day are all the greatest hits of the museum, boldly presented on the wall or within nooks under foot. In fact, one modern treasure -- Keith Haring's whimsical ceiling from the Pop Shop -- hangs above the ticket booth. To find this just several feet from Gouverneur Morris's wooden leg and the dueling guns of Hamilton and Aaron Burr makes for a grand and innovative statement.

Finally, the NYHS makes a hard turn for the modern. The Robert H. Smith Auditorium now shows 'New York Story', whisking through New York history with lighting effects, constantly moving screens and a projection of almost IMAX-like proportions. (I was genuinely surprised we didn't get those 4-D effects like rain mist and soap bubbles, but then that would ruin the fancy new auditorium seating.)

A new 'sculpture court' showcases a spectacular rarity (a Revolutionary-War era Torah) while the children's museum downstairs has been heavily revised and seems a genuinely fun experience. A scarlet-hued first-floor gallery presents the NYHS's greatest paintings more accessibly than before. Upstairs are three new exhibitions, and of course, still on the fourth is the quirky, oddly charming Henry Luce III Center for the Study of American Culture, essentially the most meticulously arranged attic in the city.

For more information visit their website: New York Historical Society. The museum is open until 8pm on Friday nights and now you can dine at a Stephen Starr restaurant there, Caffe Storico.

Friday, November 11, 2011

J. Edgar Hoover parties at New York's hottest nightclub

Work hard, play hard: The FBI director in his early days

There are at least three scenes in the new Clint Eastwood-directed J. Edgar Hoover biopic 'J. Edgar' set in New York, one of which might surprise you.

The first features Hoover on Ellis Island, but he's hardly there to greet new arrivals. The FBI director's early career was spent ferreting out and deporting anarchists, and his biggest target was Emma Goldman. On October 27, 1919, Goldman was put on trial at Ellis -- in the film, the Statue of Liberty stands at odds in the background -- and she was eventually expelled from the United Statues using a tenuous interpretation of the status of her American citizenship.

The second scene, depicting the rural Bronx of 1933, typified Hoover's career in the 1930s as a stiffly facaded embodiment of law enforcement. Here the movie envisions the arrest of Bruno Hauptmann, accused kidnapper of the child of Charles Lindburgh. Hoover's interest in the case represented an expansion of federal powers for the agency, even if Hoover's actual involvement is questionable.

But it's the third view of old New York that I found more intriguing. Hoover was a teetotaler early in life and demanded his agents aspire to clean, moral living. So its interesting that he -- and his companion Clyde Tolson -- were regular habitues at New York's hottest nightclub of the 1930s -- the Stork Club.

Sherman Billingsley, a former bootlegger, would have been made Hoover's enemy list during Prohibition. Instead, he regularly hosted the FBI director as his swanky club at 3 East 53rd Street (at Fifth Avenue).

Hoover schmoozed here with people who were useful to him, journalists like Walter Winchell who assisted with the capture of most-wanted criminals from his banquette in the Cub Room. The unscrupulous columnist was instrumental in the surrender of Louis "Lepke" Buchalter, leader of the mob's assassination unit Murder Inc., and helped play up the image of Hoover's G-Men to his millions of readers. In return, Hoover sometimes provided Winchell with FBI employees as bodyguards or drivers.

Winchell and others considered the Stork Club an invaluable nexus of social connections, and Hoover too made it his hangout when he was in town, often downing champagne and chatting with glitterati. The director was so associated with the nightclub in the 1930s, Tolson at his side, that adversaries sometimes called him 'the Stork Club detective'.

In a telling incident a few years later, in 1951, iconic entertainer Josephine Baker was denied service at the Stork Club. She filed a complaint with the police department, and supporters organized a protest outside the nightclub (pictured at right). When it was recommended that Hoover intervene on the behalf of Baker, he replied, "I don't consider this to be any of my business." [source]

Here's a collection of photos of the Stork Club with musical accompaniment. Mr. Hoover appears in one image around minute 2:40:

Stork Club logo courtesy Daddy O's Martini blog

There are at least three scenes in the new Clint Eastwood-directed J. Edgar Hoover biopic 'J. Edgar' set in New York, one of which might surprise you.

The first features Hoover on Ellis Island, but he's hardly there to greet new arrivals. The FBI director's early career was spent ferreting out and deporting anarchists, and his biggest target was Emma Goldman. On October 27, 1919, Goldman was put on trial at Ellis -- in the film, the Statue of Liberty stands at odds in the background -- and she was eventually expelled from the United Statues using a tenuous interpretation of the status of her American citizenship.

The second scene, depicting the rural Bronx of 1933, typified Hoover's career in the 1930s as a stiffly facaded embodiment of law enforcement. Here the movie envisions the arrest of Bruno Hauptmann, accused kidnapper of the child of Charles Lindburgh. Hoover's interest in the case represented an expansion of federal powers for the agency, even if Hoover's actual involvement is questionable.

But it's the third view of old New York that I found more intriguing. Hoover was a teetotaler early in life and demanded his agents aspire to clean, moral living. So its interesting that he -- and his companion Clyde Tolson -- were regular habitues at New York's hottest nightclub of the 1930s -- the Stork Club.

Sherman Billingsley, a former bootlegger, would have been made Hoover's enemy list during Prohibition. Instead, he regularly hosted the FBI director as his swanky club at 3 East 53rd Street (at Fifth Avenue).

Hoover schmoozed here with people who were useful to him, journalists like Walter Winchell who assisted with the capture of most-wanted criminals from his banquette in the Cub Room. The unscrupulous columnist was instrumental in the surrender of Louis "Lepke" Buchalter, leader of the mob's assassination unit Murder Inc., and helped play up the image of Hoover's G-Men to his millions of readers. In return, Hoover sometimes provided Winchell with FBI employees as bodyguards or drivers.

Winchell and others considered the Stork Club an invaluable nexus of social connections, and Hoover too made it his hangout when he was in town, often downing champagne and chatting with glitterati. The director was so associated with the nightclub in the 1930s, Tolson at his side, that adversaries sometimes called him 'the Stork Club detective'.

In a telling incident a few years later, in 1951, iconic entertainer Josephine Baker was denied service at the Stork Club. She filed a complaint with the police department, and supporters organized a protest outside the nightclub (pictured at right). When it was recommended that Hoover intervene on the behalf of Baker, he replied, "I don't consider this to be any of my business." [source]

Here's a collection of photos of the Stork Club with musical accompaniment. Mr. Hoover appears in one image around minute 2:40:

Stork Club logo courtesy Daddy O's Martini blog

Posted by

TUTULAE

Labels:

Charles Lindburgh,

Ellis Island,

Friday Night Fever,

Josephine Baker,

mafia,

Stork Club,

Walter Winchell

Thursday, November 10, 2011

The week New York smelled more awful than usual

Above: a typical scene during the Garbage Strike of 1911

New York street cleaners and garbage workers (sometimes referred to as 'ashcart men') went on strike on November 8, 1911, over 2,000 men walking off their jobs in protest over staffing and work conditions.

More importantly, that April, the city relegated garbage pickup to nighttime shifts only, and cleaners often worked solo. This may have been acceptable in warmer weather, but winter was approaching. At a union rally that evening, a union representative proclaimed, "A 200-pound can was a mighty big load for one man to lift into a garbage wagon ....... [Our] men are already falling ill with pneumonia and rheumatism and ... they demanded the right to work in the sunlight and the warmer weather of the daytime."

By Nov. 11, garbage was heaped along street corners, and coal ash swirled into the street, creating a blackened, smelly stew in the streets. The city brought in temporary workers to carry off the more egregious piles of filth away, but harangues and violence by union protesters required they be protected by police.

New Yorkers had lived through such a strike before, as recently as 1907, but strikers found little public support this time around. Newspapers, little sympathetic to the strikers, highlighted the growing threat of disease and the perceived selfishness of the workers. "The right to strike of public employees, who enjoy the advantage of being listed in the civil service, is more than doubtful," said the New York Times.

During bouts between strikebreakers and police, over two dozen people were injured and one man was even killed by a falling chimney. Meanwhile, Mayor William Jay Gaynor was resolute in rejecting the cleaners demands. The efforts of the workers failed, and many went back to their jobs the next week, some heavily penalized for their participation in the strike.

Below: the city shipped in workers from out of town to sweep the streets during the strike

Wednesday, November 9, 2011

Forgotten New York, city explorations, with a new look!

I interrupt this blog to insert an endorsement for one of my favorite New York City resources. We got our start here at The Bowery Boys: NYC History over five years ago, and the folks over at Forgotten New York were the first to provide links to our website and podcasts. We are continually grateful for their support. Hopefully, if you've reading this, you're probably already familiar with their work (including their invaluable guide book, Forgotten New York: Views of a Lost Metropolis.) But they've recently redesigned and reorganized their website, so I encourage you to check them out again if it's been awhile.

Forgotten New York is an addictive urban archaeology source, with regular tours of neighborhoods and photo essays that cover the area's history, architecture and culture. I also highly consider trying out one of their guided tours -- comprehensive, exhaustive and fascinating, although not for the weak of sole. Their newest tour this weekend (more information here) explores Manhattan's Hudson Riverfront, from the Battery to the Intrepid!

Forgotten New York is an addictive urban archaeology source, with regular tours of neighborhoods and photo essays that cover the area's history, architecture and culture. I also highly consider trying out one of their guided tours -- comprehensive, exhaustive and fascinating, although not for the weak of sole. Their newest tour this weekend (more information here) explores Manhattan's Hudson Riverfront, from the Battery to the Intrepid!

Posted by

TUTULAE

Tuesday, November 8, 2011

Fight of the Century: Madison Square Garden, March 8, 1971

It might have saturated the media with mountains of preemptive hype (such as the spectular Life Magazine cover above), but few would argue that the 'Fight of the Century' at Madison Square Garden didn't live up to its high expectations. On the date of that much anticipated battle, a packed Garden watched as Joe Frazier become the first man to beat Muhammad Ali. A recent countdown of the greatest moments in Madison Square Garden ranked the fight as the third greatest event in the venue's history.

Frazier recollected later: "At the time they believed he [Ali] was the greatest, but I was a little piece of leather well put together."

Frazier died yesterday in Philadelphia at age 67.

Courtesy LIFE Magazine

Monday, November 7, 2011

On 'The Band Wagon': Grand glamour in a Great Depression

How about a little music for your Monday? I was flipping through some old photographs in the New York Public Library's Performing Arts/Billy Rose Theatre Division archive and came across some striking images from the musical 'The Band Wagon', which opened on Broadway eighty years ago.

The stage musical inspired a more famous Vincent Minnelli film, through the original was also a success when it debuted at the New Amsterdam Theatre in June 1931, a glittering, bejeweled distraction bowing in one of the worst years of the Great Depression. America was hit with staggering unemployment that year (15.9 percent), unsettled by a springtime banking crisis and paralyzed by a near-stagnant Congress. New York state was so badly hit that Governor Franklin Delano Roosevelt, using emergency powers, set up an $20 million unemployment fund, one of the first of its type in America and a harbinger of programs he would employ as president.

I mention this strangely familiar backdrop to underscore how spectacularly luxurious these 'Band Wagon' sets must have been to audiences in 1931. This was a time when entertainment was becoming ever more escapist, more refined. These sets reflected the allure of musical revue as a ravishing fantasy, echoed in the songs by Arthur Schwartz and Howard Dietz. Backstage, however, the show's producers were panicking. Theaters were closing and ticket prices were being slashed (primo orchestra seats for $2.50!) as the financial crisis infiltrated every aspect of the New York entertainment business. 'The Band Wagon' closed in January 1932; as did a great many Broadway productions that year, almost two-thirds of them.

But in 1931, Fred Astaire and his sister Adele were still hoofin' it here. Amongst the other dancing tuxedos of 'The Band Wagon' was another star, Frank Morgan, who would sweep off to Hollywood by the end of the decade to portray the Wizard of Oz.

These sets were designed by Albert R. Johnson, who decorated Broadway stages well into the 1960s.

Had you been one of those cashpoor audience members who scored a ticket to a performance, this song would have helped you forget your troubles:

Pictures courtesy the NYPL Billy Rose Theatre Division

Friday, November 4, 2011

'Stieglitz and His Artists' now at the Metropolitan Museum: New York City's obsession with modern art begins here

At the Metropolitan Museum of Art, several feet from the galleries that once held the museum's colossally successful Alexander McQueen show, sits a fascinating new show that could be described as a hard sell. While exploring the galleries, I had many rooms to myself, a far cry from being sandwiched into the McQueen rooms with thousands of other people, gawking amazed at dresses made of feathers. 'Stieglitz and His Artists' will not inspire buzz, but it will delight New York history lovers.

Alfred Stieglitz (at right, photographed by Steichen) is one of America's great masters of photography, pairing reality and romanticism to frame our perception of modern life in the Gilded Age. His images of New York are iconic, severe, haunting, often luminous. But this isn't a show about these talents.

Stieglitz was also an early connoisseur and a patron of burgeoning new ideas about art. The Met's new show 'Stieglitz and His Artists: Matisse to O'Keeffe' bears witness to his bold curation of what would become modern art in its early incarnation.

It's so exact in its presentation that it makes for only a fair artistic experience. But as an abstract diorama of a particular moment in New York history, it's dynamic, the kind of show that demands you strap on an Audio Guide and take in everything within context. For a museum that excels in both art and history, this show combines both.

Most of the art here once hung in a small gallery owned by Stieglitz at 291 Fifth Avenue (at 31st Street), once the studio of photographer Edward Steichen, creator of my favorite photograph of New York City ever -- 1904's 'The Flatiron', of which two prints are on display here. Stieglitz wanted to both educate and dazzle, violently rebelling against common artistic tastes, dominated at this time by the Met itself. (The curators don't shy at poking fun at themselves in depicting Stieglitz's distaste for the museum.)

Stieglitz's gallery was the first in America to feature Pablo Picasso, Paul Cezanne, Henri Matisse and Auguste Rodin, pieces that in total would fetch billions of dollars on the art market today. Back then, they were hardly seen as financial opportunities. The art stunned and confused people, this being the days before the great Armory Show of 1913, which would permanently inject modern art into the lives of New Yorkers.

Despite the subtitle, the show primarily draws its focus onto Stieglitz's less famous contributors, with individual galleries devoted to Marsden Hartley, John Marin, and Arthur Dove. These may be less interesting to casual museum goers, but it's here that the show hits its stride as a historical document of early American taste and experimentation.

Despite the spacious rooms of the Met, it's with these lesser marquis names that you'll get the feel of what it might have been like to enter Stieglitz's galleries, the small revolutions that must have taken place with each new show. Some of this art isn't spectacular. The point of the show isn't to wow you with striking pieces but to describe a certain way of thinking at its contours. Upon his gallery walls, Stieglitz was literally asking himself, "How far can we push this? What sensibilities can we upturn?"

Not that there aren't a few well-known works mixed in here. Obviously my favorites are some of the early abstract depictions of New York, from Marin's broken-pose drawings of the Woolworth Building (one pictured at left) to Charles Demuth's mysterious 'I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold'.

Naturally the show ends with Stieglitz's greatest discovery, his own wife Georgia O'Keeffe. Known for her provocative floral and desert imagery, O'Keeffe was the subject of a number of Stieglitz gallery shows, and even the subject of her husband's own photography. The show ends with an O'Keefee painting you may not be familiar with -- her somber inspection of the East River, painted in 1928 from her room at the Hotel Shelton (at Lexington Ave and 49th Street).

As I mentioned, I'm an audio guide junkie, and this show definitely requires it unless you're well versed in the art scene of a hundred years ago. Throw on your favorite McQueen original and stroll through here some afternoon.

'Steiglitz and His Artists: Matisse to O'Keeffe' runs until January 2, 2012. Visit their site for more information.

Alfred Stieglitz (at right, photographed by Steichen) is one of America's great masters of photography, pairing reality and romanticism to frame our perception of modern life in the Gilded Age. His images of New York are iconic, severe, haunting, often luminous. But this isn't a show about these talents.

Stieglitz was also an early connoisseur and a patron of burgeoning new ideas about art. The Met's new show 'Stieglitz and His Artists: Matisse to O'Keeffe' bears witness to his bold curation of what would become modern art in its early incarnation.

It's so exact in its presentation that it makes for only a fair artistic experience. But as an abstract diorama of a particular moment in New York history, it's dynamic, the kind of show that demands you strap on an Audio Guide and take in everything within context. For a museum that excels in both art and history, this show combines both.

Most of the art here once hung in a small gallery owned by Stieglitz at 291 Fifth Avenue (at 31st Street), once the studio of photographer Edward Steichen, creator of my favorite photograph of New York City ever -- 1904's 'The Flatiron', of which two prints are on display here. Stieglitz wanted to both educate and dazzle, violently rebelling against common artistic tastes, dominated at this time by the Met itself. (The curators don't shy at poking fun at themselves in depicting Stieglitz's distaste for the museum.)

Stieglitz's gallery was the first in America to feature Pablo Picasso, Paul Cezanne, Henri Matisse and Auguste Rodin, pieces that in total would fetch billions of dollars on the art market today. Back then, they were hardly seen as financial opportunities. The art stunned and confused people, this being the days before the great Armory Show of 1913, which would permanently inject modern art into the lives of New Yorkers.

Despite the subtitle, the show primarily draws its focus onto Stieglitz's less famous contributors, with individual galleries devoted to Marsden Hartley, John Marin, and Arthur Dove. These may be less interesting to casual museum goers, but it's here that the show hits its stride as a historical document of early American taste and experimentation.

Despite the spacious rooms of the Met, it's with these lesser marquis names that you'll get the feel of what it might have been like to enter Stieglitz's galleries, the small revolutions that must have taken place with each new show. Some of this art isn't spectacular. The point of the show isn't to wow you with striking pieces but to describe a certain way of thinking at its contours. Upon his gallery walls, Stieglitz was literally asking himself, "How far can we push this? What sensibilities can we upturn?"

Not that there aren't a few well-known works mixed in here. Obviously my favorites are some of the early abstract depictions of New York, from Marin's broken-pose drawings of the Woolworth Building (one pictured at left) to Charles Demuth's mysterious 'I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold'.

Naturally the show ends with Stieglitz's greatest discovery, his own wife Georgia O'Keeffe. Known for her provocative floral and desert imagery, O'Keeffe was the subject of a number of Stieglitz gallery shows, and even the subject of her husband's own photography. The show ends with an O'Keefee painting you may not be familiar with -- her somber inspection of the East River, painted in 1928 from her room at the Hotel Shelton (at Lexington Ave and 49th Street).

As I mentioned, I'm an audio guide junkie, and this show definitely requires it unless you're well versed in the art scene of a hundred years ago. Throw on your favorite McQueen original and stroll through here some afternoon.

'Steiglitz and His Artists: Matisse to O'Keeffe' runs until January 2, 2012. Visit their site for more information.

Wednesday, November 2, 2011

Soooo, about that new HBO Robert Moses movie.....

You've probably heard by now that Oliver Stone is preparing to make a film version of Robert Caro's 'The Power Broker', the iconic biography of New York's influential city planner Robert Moses. Several people have emailed us for our reaction to Moses's big-screen debut. (Well, small screen actually. It's an HBO film.) The 'master builder' is a regular foil in our podcasts. Our 100th episode is devoted to Moses' influence on the city.

But a movie? I'm cautiously optimistic to mildly apprehensive, as anybody should be when a classic book is adapted for the screen. 'The Power Broker' is over 1,100 pages long. For comparison sake, The Lord of the Rings is 1,216 pages, and director Peter Jackson stretched that over three long, epic films. The Caro book also charts about seven decades or so. Will the man's career -- not to mention the history of 20th century New York -- acceptably fit into a single movie?

And this presumably wouldn't be a normal bio pic, because 'The Power Broker' isn't a normal bio. The book defined Moses in the public consciousness; it both sullied and mythologized him, during his lifetime. Caro's screed is part of the Robert Moses story now. People either support its view that Moses did more harm than good to New York City, or they rebel against it.

Now take that provocative text and hand it over to a director, born and raised in New York, who has proven, time and again, to create extraordinary cinema doused in an unashamed political point of view. Stone is fearless, if not consistent; after all, his last two forays into New York were 'World Trade Center' and the sequel to 'Wall Street', films as ambitious as they were mildly received. The combination of Caro's angst and Stone's audacity will certainly be combustible.

Why now? I suspect one element that will appeal to modern audiences is the image of Moses as a man who could get things done, a phrase that Caro applies as a double-edged slogan. Moses's agile political maneuvers and his use of funds (first from the federal government, then from various public authorities) to sculpt grand projects makes the stranglehold of modern politics seem truly anemic.

If HBO does a strict adaptation, don't expect to see Jane Jacobs. She appears nowhere in the book. But I suspect they'll insert a new section into the film, as the Robert Moses vs. Jane Jacobs trope is impossible to resist. Can't you already picture a scene with young Jacobs (perhaps played by Laura Linney or Robin Wright) leading a protest against LOMAX with picketers in Washington Square? Although if they really want to put the parks commissioner against a feisty female preservationist, there's plenty of material regarding his duels in the press with Eleanor Roosevelt.

On the subject of casting, I've heard the name Frank Langella tossed around for the lead role. But he's in his 70s. The most fiery and interesting scenes -- the most filmic ones -- take place with Robert Moses in his early to mid 40s. Revisit the scene with Moses scouring the beaches of the Long Island south shore, imagining a great public beach. What tall, brawny, 40ish actor fits the bill?

I'm almost more fascinated in seeing who gets cast as the two pivotal mayors of the book -- Fiorello LaGuardia and John Lindsay. Realistically, is there any human being (excepting Danny Devito) that fits the unusual physical requirements of LaGuardia?

But perhaps the most interesting depiction will be of New York itself, as we'll certainly be greeted with the construction of mighty projects like the Triborough Bridge and devastating neighborhood killers like the Cross Bronx Expressway. How will the film convey a public uprising against Moses-style urban growth that in reality took decades to effectively organize?

I do hope the movie indulges in a little fantasy as well, depicting the city of Moses's dreams, with lower Manhattan cut through with elevated highways, New York Harbor cleaved with a bridge from Battery to Brooklyn, and miles of glorious parking lots. After all, who doesn't love a good horror movie?

But a movie? I'm cautiously optimistic to mildly apprehensive, as anybody should be when a classic book is adapted for the screen. 'The Power Broker' is over 1,100 pages long. For comparison sake, The Lord of the Rings is 1,216 pages, and director Peter Jackson stretched that over three long, epic films. The Caro book also charts about seven decades or so. Will the man's career -- not to mention the history of 20th century New York -- acceptably fit into a single movie?

And this presumably wouldn't be a normal bio pic, because 'The Power Broker' isn't a normal bio. The book defined Moses in the public consciousness; it both sullied and mythologized him, during his lifetime. Caro's screed is part of the Robert Moses story now. People either support its view that Moses did more harm than good to New York City, or they rebel against it.

Now take that provocative text and hand it over to a director, born and raised in New York, who has proven, time and again, to create extraordinary cinema doused in an unashamed political point of view. Stone is fearless, if not consistent; after all, his last two forays into New York were 'World Trade Center' and the sequel to 'Wall Street', films as ambitious as they were mildly received. The combination of Caro's angst and Stone's audacity will certainly be combustible.

Why now? I suspect one element that will appeal to modern audiences is the image of Moses as a man who could get things done, a phrase that Caro applies as a double-edged slogan. Moses's agile political maneuvers and his use of funds (first from the federal government, then from various public authorities) to sculpt grand projects makes the stranglehold of modern politics seem truly anemic.

If HBO does a strict adaptation, don't expect to see Jane Jacobs. She appears nowhere in the book. But I suspect they'll insert a new section into the film, as the Robert Moses vs. Jane Jacobs trope is impossible to resist. Can't you already picture a scene with young Jacobs (perhaps played by Laura Linney or Robin Wright) leading a protest against LOMAX with picketers in Washington Square? Although if they really want to put the parks commissioner against a feisty female preservationist, there's plenty of material regarding his duels in the press with Eleanor Roosevelt.

On the subject of casting, I've heard the name Frank Langella tossed around for the lead role. But he's in his 70s. The most fiery and interesting scenes -- the most filmic ones -- take place with Robert Moses in his early to mid 40s. Revisit the scene with Moses scouring the beaches of the Long Island south shore, imagining a great public beach. What tall, brawny, 40ish actor fits the bill?

I'm almost more fascinated in seeing who gets cast as the two pivotal mayors of the book -- Fiorello LaGuardia and John Lindsay. Realistically, is there any human being (excepting Danny Devito) that fits the unusual physical requirements of LaGuardia?

But perhaps the most interesting depiction will be of New York itself, as we'll certainly be greeted with the construction of mighty projects like the Triborough Bridge and devastating neighborhood killers like the Cross Bronx Expressway. How will the film convey a public uprising against Moses-style urban growth that in reality took decades to effectively organize?

I do hope the movie indulges in a little fantasy as well, depicting the city of Moses's dreams, with lower Manhattan cut through with elevated highways, New York Harbor cleaved with a bridge from Battery to Brooklyn, and miles of glorious parking lots. After all, who doesn't love a good horror movie?

Tuesday, November 1, 2011

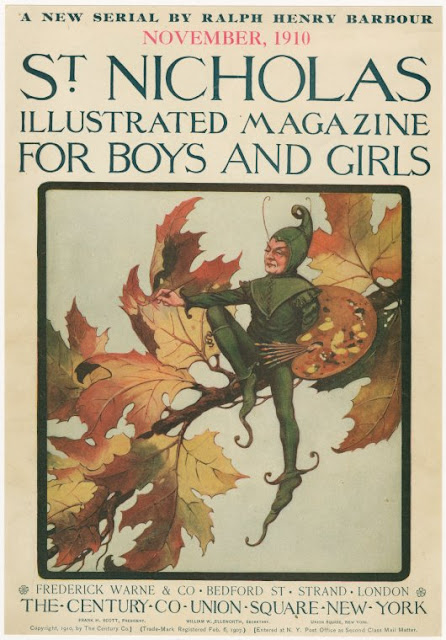

Autumn Illustrated: A publishing house in Union Square

Have a little fall color, courtesy a 101-year-old edition of one of America's most important childrens literary magazines. St. Nicholas Illustrated Magazine, filled with full-color artwork, contests and short stories by prominent writers like Mark Twain and Louisa May Alcott, was created by Charles Scribner's publishing company in 1873, notable for employing one of the first powerful female editors -- Mary Mapes Dodge.

By 1910, it was distributed by the Century Company, another publishing house located on Union Square, next door to the once-great Everett House. The Century's swanky office building is still around today, as a retail space for Barnes & Noble.

Magazine cover courtesy NYPL

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)